Restorative Justice Competency Building in the IDG

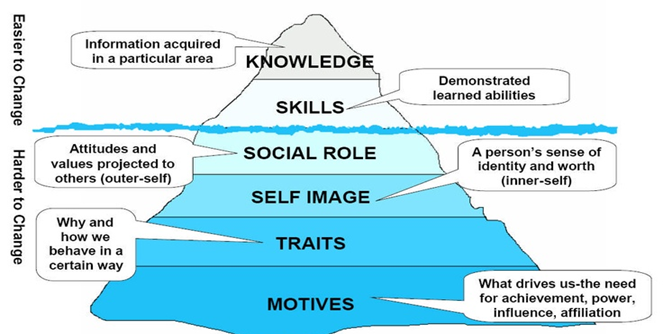

The Insight Development Group is informed by the iceberg model of competency building. Knowledge and skills, the visible parts of the iceberg are the easiest elements to change, while the items below the iceberg that drives the person’s attitude are harder to change. Actions in the world are driven less by knowledge and skills and more by values, attitudes, and mindsets. The former are tools, the latter is the one that fuels behavior and decision making. Often times, competency building narrowly focuses on developing only the visible parts of the competency iceberg. The IDG curriculum and implementation design specifically targets all areas of the competency iceberg.

Moral Development and the Psychology of Restorative Justice

The principles, values, and practices of restorative justice are motivated by expanded stages of moral development. Restorative justice is a paradigm of justice grounded in principles of egalitarianism, humanism, and global ethics. To develop core competencies in these areas, IDG has designed a curriculum specifically aimed at expanding moral developmental growth through processes of transformative and dialogic learning. Cultivating self-awareness around the driving forces behind personal values, attitudes, and mindsets are integral in understanding moral emotions, and moral behavior. Engaging in restorative processes and behaviors requires a moral developmental understanding of stages 5-6 on the moral developmental scale.

Our Program Offerings

Restorative Justice Intensive Competency Course: 33- Weeks

Intro to Restorative Justice: 8-Weeks

Intro to Restorative Justice Competency: 8-Weeks

Restorative Ecology & Prisons: 12-Weeks

Restorative Justice Facilitator Training Workshops

Restorative Justice Peer-Mentor Training Workshops

Intro to Restorative Justice: 8-Weeks

Intro to Restorative Justice Competency: 8-Weeks

Restorative Ecology & Prisons: 12-Weeks

Restorative Justice Facilitator Training Workshops

Restorative Justice Peer-Mentor Training Workshops